Credit: skrbd.org

Your pain is the breaking of the shell that encloses

your understanding.Even as the stone of the fruit must break, that its

heart may stand in the sun, so must you know pain.

So begins Kahlil Gibran’s poem, “On Pain.” Human beings are naturally averse to pain. This is to be expected, as pain is often an indicator of a condition that is antithetical to thriving or even survival. Here, Gibran seems to be referencing emotional and mental pain as opposed to physical pain, stating,

Much of your pain is self-chosen.

It is the bitter potion by which the physician within

you heals your sick self.

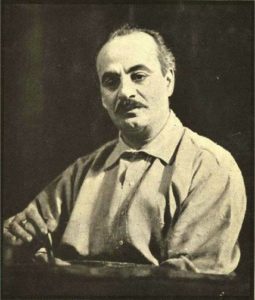

Poet Khalil Gibran

(Credit: voiceseducation.org)

Pain and its twin, suffering, come into nuanced relationship in this poem if we consider pain — emotional, mental, or physical — as a symptom of something external to one’s own body and mind, the result of an action, or a reactive condition. Suffering, on the other hand, is a response to pain, as much as contentment and surrender to unchangeable conditions could also be a response. Gibran writes of that choice:

[C]ould you keep your heart in wonder at the

daily miracles of your life, your pain would not seem

less wondrous than your joy;And you would accept the seasons of your heart,

even as you have always accepted the seasons that

pass over your fields.

To accept your pain instead of resisting, denying, or demonizing it creates a space for conscious choice to come through: to suffer or to abide with awareness, and learn (“And you would watch with serenity through the / winters of your grief”). Gibran urges us to meet our pain with clarity and curiosity, asking ourselves what is being revealed within us when pain cracks open our narratives, routines, and sense of self, much as the stone of a fruit is cracked open by the forces of nature. If we can trust that our pain is present to direct our attention to how we need to grow closer to our truth and purpose, it becomes a bitter medicine:

Credit: pinterest.com

Therefore trust the physician, and drink his remedy

in silence and tranquillity:For his hand, though heavy and hard, is guided by

the tender hand of the Unseen,And the cup he brings, though it burn your lips, has

been fashioned of the clay which the Potter has

moistened with His own sacred tears.

If the physician is “within you,” and pain comes not from within but from the world, we can understand the “physician” as our intuition, or the intuitive faculty by which we relate to ourselves. But, who directs the physician within? Gibran tells us to “trust the physician” because that faculty is directed by the “Unseen,” which can be interpreted as the Great Mystery, Universal Soul, God, or Natural Law. In other words, the Unseen is that which is unchangeable, beyond our control, and governing our collective destiny. To relate to the Unseen is to relate to our pain: We can trust it or resist it. Either way, there is no way to avoid it, which is ultimately the best reason to absorb the full force of our reality so that we can meet it with presence and authority rather than be pulled under by the changing tides of our lives.

Find the full text of “On Pain” here.

“On Pain” by Kahlil Gibran

“On Pain” by Kahlil Gibran

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?