The 19th century poet William Cullen Bryant could not recall when he wrote “Thanatopsis.” Similarly, I long ago lost count of how many of my high school students had not thought much about their mortality before we turned to the poem in our American Literature anthology. It caught their attention that he was their age — 17 — when he penned it (a detail recalled by a college friend of the poet).

The 19th century poet William Cullen Bryant could not recall when he wrote “Thanatopsis.” Similarly, I long ago lost count of how many of my high school students had not thought much about their mortality before we turned to the poem in our American Literature anthology. It caught their attention that he was their age — 17 — when he penned it (a detail recalled by a college friend of the poet).

That alone got the 17-year-olds in front of me thinking. They also immediately empathized with the poet upon finding out the poem was published in the North American Review in September 1817, after Bryant’s father showed it to the journal’s editor — without his son’s knowledge.

The title always had them scratching their heads. “Thana – what -sis?” one would invariably ask.

“Thanatopsis, from the Greek word that means ‘meditation on or contemplation of death,'” I’d reply. And then we’d start contemplating its smooth, deceivingly comfortable start.

To him who in the love of Nature holds

Communion with her visible forms, she speaks

A various language; for his gayer hours

She has a voice of gladness, and a smile

And eloquence of beauty, and she glides

Into his darker musings, with a mild

And healing sympathy, that steals away

Their sharpness…

Teens like the simple connection to Nature the elegy opens with — after that Greek mumble of a title .“It’s like ‘The Giving Tree,’” I remember one saying. “Nature gives us what we need.”

Then the voice of the poem abruptly switches its focus to dying:

When thoughts

Of the last bitter hour come like a blight

Over thy spirit,

From the deathbed, the poem moves on to the end of life and interment. That oneness with Nature established earlier in the elegy becomes more literal in the grave.

Earth, that nourished thee, shall claim

Thy growth, to be resolved to earth again,

And, lost each human trace, surrendering up

Thine individual being, shalt thou go

To mix for ever with the elements,

To be a brother to the insensible rock

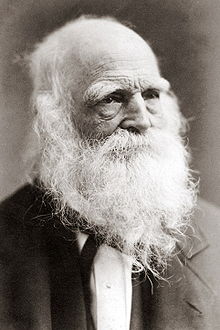

William Cullen Bryant

This is where some in the class might get a bit squeamish, but a careful reader would be sure to bring out,“But that’s just where he says our body goes. This guy says our spirit will find some comfy place with a bunch of rich people, kings, and good looking people. The way he describes it reminds me of the woods in Harry Potter.”

Yet not to thine eternal resting-place

Shalt thou retire alone, nor couldst thou wish

Couch more magnificent. Thou shalt lie down

With patriarchs of the infant world—with kings,

The powerful of the earth—the wise, the good,

Fair forms, and hoary seers of ages past,

All in one mighty sepulchre.

Other students, have said it sounded like a royal wedding or the Wizard’s Oz, even Bambi’s forest. Whatever images Bryant’s landscape of death conjured in their mind, it would be remarkable to witness their responses to a long-gone poet’s musings and have them raise questions about what happens after we die.

As we continued, “Thanatopsis” made all of us aware that we are equals in the way we must face the unknown, no matter our backgrounds or abilities. And most important, it gave us a prescription for the gift of life that remains until we are face to face with death in its last stanza.

So live, that when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, which moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave,

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.

If you’d like to read the entire poem, go to the Poetry Archive.

“Thanatopsis” by William Cullen Bryant

“Thanatopsis” by William Cullen Bryant

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull