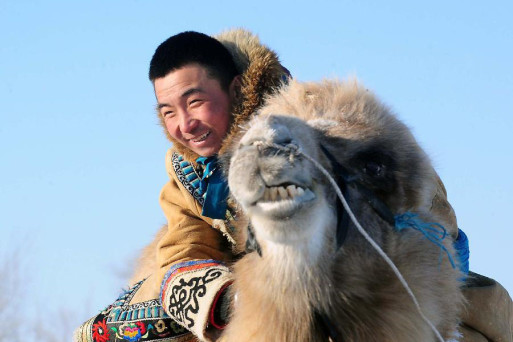

For thousands of years, the nomads of Mongolia have roamed the steppes of Central Asia, carrying their belongings and setting up their tents, called “gers,” on the harsh, inhospitable land. One of the last remaining nomadic cultures on Earth, these Mongol people maintain many of their ancient traditions and customs, including a deep, abiding respect for nature and all forms of life. To this day, they believe that desecrating the earth or killing any living thing is a sin.

Credit: China National Tourism Administration

The religion of the nomads is a unique blend of Tibetan Buddhism and shamanism. Replete with rituals, superstitions and multiple deities, their complex belief system includes the practice of excarnation–leaving the bodies of the dead in the open air to be eaten by scavengers. In the Mongolian belief system, this open air sacrifice, or “sky burial” is the final virtuous act of the person who has died–his last gift to the world.

The practice of sky burial, or “Ködägäläkü” (literally: “to deposit a corpse in the steppe”) dates back to the 16th century, when the ruler Altan Khan declared Buddhism the national religion of Mongolia and outlawed the ancient practice of burying the dead in the ground with the sacrificed remains of animals, servants or wife of the person who had died. Because the steppes are virtually devoid of trees, cremation was reserved for high-ranking priests and people who had died from infectious diseases. Thus, the tradition of sky burial became the norm. Although it and all other religious practices were outlawed by the Communist regime in the 1930s, it is still widely practiced by the nomads today.

Credit: pinterest.com

Traditionally, sky burials follow a very specific ritual. After a person dies, the body is prepared by a son, brother or close male relative, who is known as the “jasu bari cu,” or undertaker; no one else is allowed to touch the body in any way. The body is left unclothed so the person can leave the world as they entered it. A long piece of silk or other cloth, known as a khadak, is placed over the face.

Mongols believe that the spirits of the dead can return and cause misfortune to those who are left behind, so for some time following a death the bereaved family stands watch over the body, burning incense and butter lamps to prevent the spirit from coming back.

Mongols believe that the spirits of the dead can return and cause misfortune to those who are left behind, so for some time following a death the bereaved family stands watch over the body, burning incense and butter lamps to prevent the spirit from coming back. During this time, tribal priests say prayers to guide the person’s spirit into the next life, and burn incense and make offerings of food to ward off evil spirits. When the priests determine that the person’s spirit is ready to move on, the funeral is arranged.

Prior to “burial,” the person who has died is dressed in white clothing and taken — often on horseback — to the tribal “cemetery,” typically a remote area inhabited by carrion birds and wild dogs. There, the body is placed on the ground with the head facing north — the direction of the next world — and the mourners leave.

The family returns after three days: If the person’s body has been completely devoured, they believe his spirit has been released and can once again return to the world in a new form. If any part of the body remains, they return again at weekly intervals until it is gone.

Credit: thedurangoherald.com

For the nomads of Mongolia, the practice of sky burial is a part of a long tradition of revering and preserving life: by feeding the wild animals of the steppes with the remains of the dead, they both sustain the predators and protect their prey. Perhaps more importantly, the tradition is also a profound affirmation of the Buddhist concept of the impermanence of all things. The body, in this view, is simply a vessel. Once it lives no more, its purpose is to nurture and nourish the Earth and those who are left behind.

The Ancient Practice of Sky Burial

The Ancient Practice of Sky Burial

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States