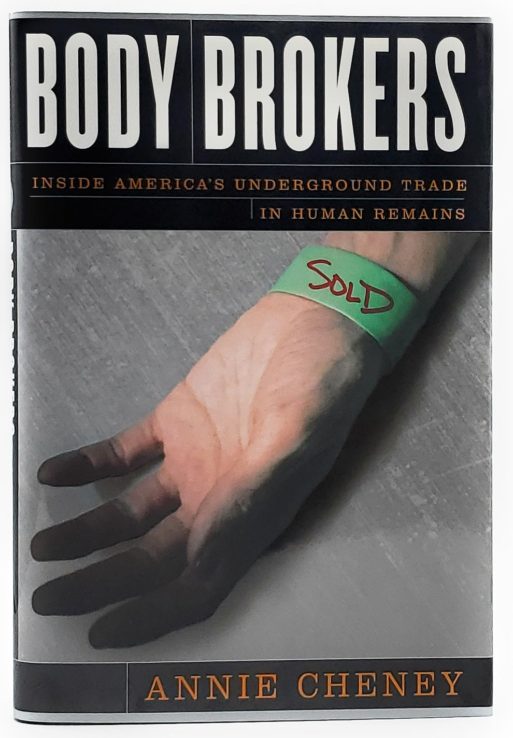

It’s hard to imagine subject matter more cringe-worthy than the for-profit tissue and body business. Perhaps this explains the relative obscurity of Annie Cheney’s “Body Brokers: Inside America’s Underground Trade in Human Remains,” a muckraking exposé on this for-profit, shockingly lucrative industry. Upon the book’s release, publications around the country gave it generally favorable reviews, and predicted that it should blow the lid off of this subject. But it never happened. “Body Brokers” is a slim book at 193 pages, expanded from a piece Cheney wrote for Harper’s, perhaps the first significant investigation into this issue. Since then, it has also been the last.

It’s hard to imagine subject matter more cringe-worthy than the for-profit tissue and body business. Perhaps this explains the relative obscurity of Annie Cheney’s “Body Brokers: Inside America’s Underground Trade in Human Remains,” a muckraking exposé on this for-profit, shockingly lucrative industry. Upon the book’s release, publications around the country gave it generally favorable reviews, and predicted that it should blow the lid off of this subject. But it never happened. “Body Brokers” is a slim book at 193 pages, expanded from a piece Cheney wrote for Harper’s, perhaps the first significant investigation into this issue. Since then, it has also been the last.

This is not for lack of talent on Cheney’s part. If a bit over-wrought at times, “Body Brokers” is engaging, fast-paced, and informative without being didactic. Most readers will be surprised that for-profit companies facilitate a large part of a non-profit tissue or body donation. And these companies make an, erm, killing off of them.

When a person agrees to donate their body or tissue following their death, this material is distributed to medical supply companies and universities around the country. This transaction has come to be enabled by middlemen called “body brokers,” individuals who locate and purchase the body or tissue, often for little more than reimbursement for a hospital’s expenses. It then sells the purchase to a third party at a huge mark up. The body brokers’ selling point is his ability to locate the tissue or body parts that meet their buyers’ demands.

This demand is vast, and growing. And oftentimes, as Cheney chronicles copiously and gruesomely in her book, the body brokers’ “connections” are not only those in the medical field, but corrupt individuals in the funeral and cremation industry who have realized the easy money they can make selling body parts taken from cadavers prior to cremation or a closed casket funeral, unbeknownst to the decedent’s family.

The first half of the book closely follows the path of one such broker, Michael Brown, a successful crematory operator who one day received a phone call from a company called Innovations in Medical Education and Technology, a firm that was attempting to supply body parts for a surgical training seminar in Southern California. After meeting with the company’s founder, a man named Augie Perna, Mr. Brown agreed to enter into a partnership with them — he would go on to expand his crematorium and open up a body donation facility in the new building. He could now offer his customers a package where they would donate their body and receive a free cremation, though not before Brown removed and stored any parts he wanted. It was, as the title of Cheney’s chapter re-states, “An Ideal Situation.” It wasn’t until several years, hundreds of thousands of dollars, and a guilty plea to 66 counts of mutilation of remains and embezzlement later, that Brown’s business was brought to a close thanks to an employee whistle-blower.

Credit:labroots.com

Cheney introduces a range of players at all stages of this field, and they assure her that it is absolutely the business to be in — that is, all those on the legal side. Because, while it seems like simple sense that a multi-million dollar industry could not be receiving all of their product from donations, no government agency enforces or regulates this market. Writes Cheney, “Unlike organ procurement organizations, tissue banks are not required to be nonprofits. No one audits their finances.”

What can begin as a nonprofit organization working in conjunction with a local medical college, can become a for-profit business providing medical supplies and implants, such as the case of Regeneration Technologies, Inc., a tissue processor in Florida which in 2003 had $75 million in revenues. If the profit motive is there, and there’s scant reason beyond morality not to partake, there seems little reason why shady practices like the ones Cheney documents shouldn’t flourish.

And of course, this is not all a bad thing. Without tissue or body donation American health care would be in a far worse place than it is now. But it does highlight a discouraging, and even dangerous lack of public stomach for these sorts of uncomfortable discussions. Cheney describes one instance where a raft of knee ligament implants supplied by a funeral home, from a cadaver that had been deceased for longer than is safe, led to violent illness and in one case a transfer patient’s death. But, as the crooked crematorium operator Michael Brown puts it, “The only regulations that stay true are the ones that someone had an aggressive conviction about, like the mother that loses her child to a drunk driver.”

Unfortunately, it is far easier for American politics to deal with over-drinking than with what happens to our bodies after we die.

Editor’s Note: Since Cheney’s book debuted, the U.S. government has done little to curb the abuses of the body-broker industry. Read our article about a company that turned a $27 million profit selling parts from donated bodies just last year.

“Body Brokers: Inside America’s Underground Trade in Human Remains,” by Annie Cheney

“Body Brokers: Inside America’s Underground Trade in Human Remains,” by Annie Cheney

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States