How expansive is the human mind? How resilient is the human spirit? These are questions few of us ask ourselves as we go about our daily lives. Yet when tragedy strikes, the answers may be crucial to our ability to survive.

How expansive is the human mind? How resilient is the human spirit? These are questions few of us ask ourselves as we go about our daily lives. Yet when tragedy strikes, the answers may be crucial to our ability to survive.

“The Diving Bell and the Butterfly” is a film that answers both of these questions. A visually stunning, achingly beautiful true story of a man who is completely paralyzed after a catastrophic stroke, it is a testament to our ability to overcome suffering when we tap into the resources of mind and heart.

The protagonist of the film is Jean-Dominique Bauby, an energetic, wildly successful journalist and editor-in-chief of the French fashion magazine, Elle. On Dec. 8, 1995, at the age of 43, Bauby suffered a massive stroke and was comatose for 20 days. When he awoke, he had locked-in syndrome, an extremely rare disorder in which the entire body is paralyzed, but the person is completely awake and alert. Speech is impossible. The only parts of the body not affected are the eyes.

We meet Bauby when he awakes in the hospital, and watch much of the movie through his one functioning eye. (Doctors sewed one eye closed to prevent infection.) We see him as he imagines himself floating weightless in dark murky water, encased in a diving bell, isolated and alone. We watch as his neurologist explains his condition, and hear his voice as he screams soundlessly that this simply cannot be real. As we watch him watch the world through a single-vision lens, we share his suffering as he comes to grips with what is now his life.

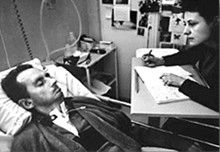

Jean-Dominique Bauby before the stroke

(Credit:dailymail.co.uk)

The movie cuts effortlessly between Bauby’s present and his past. As he begins to accept the reality of his useless body, he relies on his imagination to travel where he chooses to go. These imaginary journeys are cinematographically breathtaking, yet heartbreaking at the same time. One can only imagine the unbearable sense of helplessness and horror Bauby must have endured.

Eventually Bauby meets Claude Mendibil, a speech therapist who takes on the almost impossible task of helping him communicate. At first resistant and then hostile, Bauby eventually comes to realize that Claude is his lifeline to the outside world. She sits at his bedside, slowly reading letters of the alphabet until her patient blinks to indicate which one he wants. As they work together day after day, we see a relationship blossom that is very much like love.

With Claude at his side, Bauby eventually dictated the memoir after which the film is named. Explaining the title, he writes, “My cocoon becomes less oppressive, and my mind takes flight like a butterfly. There is so much to do. You can wander off in space or in time, set out for Tierra del Fuego or for King Midas’s court.”

The original French version of “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly: A Memoir of Life in Death” was published on March 7, 1997. It received rave reviews, and sold 25,000 copies the first day.

Jean-Dominique and Claude

(Credit: wikipedia)

Two days later, following a sudden bout with pneumonia, Bauby died.

Most of us can only begin to imagine the horror of living with locked-in syndrome — trapped in a body over which we have no control. Most of us probably believe there is no way we could endure what Jean-Dominique Bauby endured. Yet this beautiful film somehow reassures us that we are stronger and more resilient than we believe. In the words of Bauby’s journalist friend, Roussin, who visits him in the hospital and speaks about his four years in captivity in Beirut, “Hold fast to the human inside you, and you will survive.”

Whether you are grieving the loss of a loved one, or simply grappling with the emotional vagaries of this journey we call “life,” take the time to see this film. “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly” will break your heart, but it will also give you hope.

“The Diving Bell and the Butterfly” Directed by Julian Schnabel

“The Diving Bell and the Butterfly” Directed by Julian Schnabel

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States