Wonderful memories … my mom and me, checking out the new post-modern architecture on Miami Beach’s Brickell Avenue while I was in college in the 80s

This is Suzette’s story as told by Jeanette Summers. Our “Opening Our Hearts” stories are based on people’s real-life experiences. By sharing these experiences publicly, we hope to help our readers feel less alone in their grief and ultimately aid them in their healing process. In this story, Suzette talks about the experience of losing her mother to a heart attack in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and how shelter-in-place orders kept them apart in the end. Suzette had to see her dead mother at the crematorium to say goodbye.

My mother died of a heart attack at the age of 88. In spite of her age, her death wasn’t exactly expected. Nor was my need to see my mother dead at the crematorium, followed by viewing her bones in the retort.

I traveled from my home in California to my parents’ home in Florida this past holiday season. I could sense that my mother’s faculties were slipping. The earliest phases of cognitive issues were beginning to develop. She wasn’t hallucinating, wasn’t forgetting who or where she was, but she had a delay in finding some words and would often say of things in the past, “I don’t remember.” I took her to the doctor for a check-up. Test results indicated that she’d had a series of small strokes, resulting in vascular dementia.

But I truly believed I’d have at least another five years with her.

I researched my mother’s condition. Based on my findings, I had a hunch that she’d ultimately die of either a massive stroke or a heart attack. But I truly believed I’d have at least another five years with her. I was right about the cause of her death, but I was wrong when it came to the timeline I predicted. By April 1st, she was gone.

A couple of months before my mother died, I put her in a senior care facility in Florida, thinking that round-the-clock supervision and attention would be the healthiest thing for her, as well as for my father. He’s in his 90s and was suffering from a terrible depression as a consequence of caregiving and watching his wife of 70 years slowly but surely fade away. As it turns out, though, the facility I chose was a daughter’s nightmare come to life. They were treating my mother horrifically. When I found bruises on her 87-year-old body, there was no question: I absolutely, positively needed to get her out of there.

I knew I had to get my parents to my state. I had to have them close.

Around this time, the COVID-19 pandemic was starting to make its way to the United States. I had a strong feeling that a quarantine order was due to take effect in the upcoming weeks. I knew I had to get my parents to my state. I had to have them close.

My mother was admitted to a beautiful limited-bed care home here in California. I made sure she was fully settled there before I drove to Florida, packed up my father’s belongings, and drove him back to California with me so that we could all be together. Three days before I took off to collect my dad, my mother softly said, “This is the last chapter of my life” — she knew that her time was approaching.

It was then when I realized that not all of my peers had such loving parents. I was extraordinarily lucky, and I knew it.

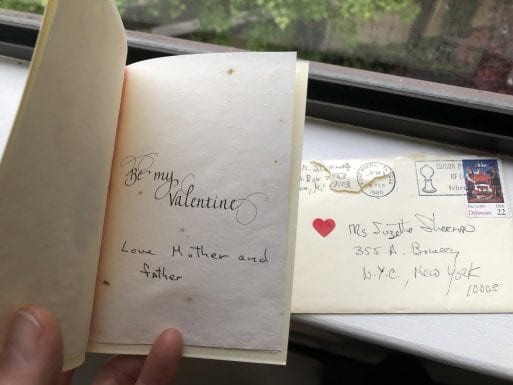

My mother was always strong and assertive — by no stretch of the imagination a pushover. But, unbelievably, she never once raised her voice to me while I was growing up. When I went away to college, she sent me a card and a little present for every holiday: Easter, Valentine’s Day, and St. Patrick’s Day, even though we weren’t even Irish. The way my mother took every possible opportunity to cultivate and spread a spirit of celebratory joy — the way she went above and beyond to show me, her only daughter, that she loved me and was always thinking of me in ways big and small — didn’t fully register until I left my childhood home. It was then when I realized that not all of my peers had such loving parents. I was extraordinarily lucky, and I knew it. I don’t think a kinder mother ever existed. But my mother’s one flaw as a parent was that she never touched me while I was growing up. I was deprived of the physical affection I craved, and I felt it every day of my childhood. I never understood it. We once shared a body. Why was she so distant in this one remarkable way?

One of the many loving cards (this one from 1988) my mom sent to me

over the years; I kept them all, and they still touch my heart

Five years ago — I was in my mid-50s at the time — I was visiting my parents at their Florida home. I suffer from severe hypoglycemia, and I experienced an acute, overnight episode while sleeping in their guest room. I knocked on my parents’ bedroom door in the middle of the night, terrified that I was about to slip into a coma. I desperately needed someone to hold me. And so, it hurt me deeply that when I hugged my mother, I could still — even as a fully grown, adult woman — feel a reticence and a rigidity in her touch.

I’d cradle my mother on the sofa for hours at a time, and for the first and only time I can remember, she’d hold me back.

When I was in Florida last year for the holidays, though, my mother allowed me to truly soften into her embrace. I’m not sure of exactly why. Maybe it was because her early-stage dementia had made her more demonstrative, less inhibited. Or maybe she, like me, had a premonition that she didn’t have very long, that this was our last chance to physically express our love as mother and daughter. But in the end, it doesn’t matter why. What matters is that it happened, and that it was beautiful. I’d cradle my mother on the sofa for hours at a time, and for the first and only time I can remember, she’d hold me back.

My mother lived at the senior care home here in California for 20 days. I’d visit her for at least two hours every day she was there. During those precious hours, I got the chance to be with her, talk to her, and — perhaps most importantly of all — continue to hold her.

But the last two times I saw my mother alive were through glass. The COVID-19 lockdown had officially taken hold. I could still visit her at the senior care home; I could see her through the house’s set of French doors and, at the same time, speak to her on the phone: a kind of simulated visit. I understand why I couldn’t touch her, but it’s still painful to me that my time to hold her was stolen. I’m thankful that we got to be in close proximity to one another, though. I noticed, through those French doors, how gorgeous her coloring was, how luminous she looked. I expressed to her on the phone, “You look beautiful.” When my father commented on her contentment at this new facility, I knew, without a doubt, that I had made the right decision — a decision that brought my mother tranquility in what turned out to be her final days.

I was in line at the grocery store when I got a phone call from the owner of the senior care home: My mother had passed out. She, like me, suffered from severe hypoglycemia, and I thought she was having an episode. “Feed her breakfast,” I directed him. “Give her protein, not carbs.”

The next phone call I got was from a hospital staff member: My mother was having a cardiac arrest.

My mother eventually came to, and the owner did as I asked. But she passed out again and threw up. She was taken to the hospital. The next phone call I got was from a hospital staff member: My mother was having a cardiac arrest. The staff member had no definitive answers to my questions. All she could tell me was that the doctor would call me back.

Right away, I phoned my brother to tell him what was happening. At first, his mind jumped to the coronavirus. At this unprecedented moment in time, it’s easy for people to associate any and all deaths, ailments, or other failings of the human body with COVID-19. I explained to him that no, our mother’s sudden hospitalization had nothing at all to do with the virus, but that things weren’t looking good. Once someone is in the middle of a “code blue,” they hardly ever come back.

My brother and I agreed that we wouldn’t tell our father — there was no reason to worry him unless the worst happened. I held out hope that that wouldn’t be the case. The doctor hadn’t phoned back yet, so I tried to keep faith that no news was good news. But sure enough, my phone rang while I was on my way home. It was the doctor — my mother had been pronounced dead.

I immediately grabbed him and whispered the devastating news in his ear, and we both sobbed, like children, in each other’s arms.

When I arrived at my house — where my father was staying with me — I immediately grabbed him and whispered the devastating news in his ear, and we both sobbed, like children, in each other’s arms.

Because of the risk of COVID-19 infection, family members weren’t permitted in the morgue. But I called the funeral director at the facility where my mother was to be cremated. He told me that I could come and witness the cremation process if I wanted to. I absolutely needed to see my dead mother one more time and say goodbye. He said to come at 9 o’clock a few mornings later and mentioned that any organic objects that had a particular significance to my mother could be incinerated along with her.

I arrived at the crematorium with an old, striped throw blanket my mother always loved and a cloth — sprayed with perfume — to protect my face and cover the possible smell.

My mom in Florida 10 years ago with her favorite striped blanket; a decade later, I would place it on her in her cardboard casket to be cremated with her

I freely admit that as badly as I wanted the closure I imagined I would get from seeing my dead mother one last time, there was a part of me that was afraid. I’ve heard some people say that seeing their lost loved ones’ inanimate corpses — their souls no longer present anywhere in the room — left them feeling disoriented, disconnected, empty and alone. That it only deepened their grief. “Am I going to regret this?” I thought to myself. “Am I making a mistake?”

When I entered the crematorium, my mother’s body was in a closed cardboard box.

“I don’t know if I can do this,” I said to the crematory operator, clutching the top of his arm to steady myself. But I knew, deep down, that I had to.

When he lifted the top of the box, I was aghast: “Oh my God,” I said. “I can’t believe how beautiful she is,” as I burst into tears. And she really, really was. The serene expression on her face. Her vibrant coloring: identical to the way it was when she was alive.

“Did they do something to her?” I asked him.

“No, they didn’t,” he said.

“Do they always look this good?”

“No, they don’t.”

I wanted to touch her skin one last time so badly, but I knew I couldn’t — because of her having been in the morgue with possible exposure to the virus. I was overwhelmed at the beauty of seeing her and didn’t want to let her go. For a split second, I almost understood why some people taxidermy their lost loved ones, something I always thought was totally insane.

My precious last picture: My mom in her endearing, childlike way,

on her 88th birthday in the lovely care home that finally gave her peace

I snipped a lock of my mother’s hair, put the striped throw blanket over her, and asked the crematory operator if I could see her toes. The staff at the Florida facility had let my mother’s toenails grow so long, they were practically curling into her skin. At the new care home — the lovely one here in California — a staff member asked my mother if she’d like a pedicure, to which she replied yes, she would. I wanted to see if my mother had gotten the pedicure she wanted. Sure enough, when the crematory operator revealed her feet to me, her toenails were neatly trimmed and painted a beautiful grey-white.

All at once, it dawned on me: My mother went peacefully — at a point before she completely lost her memory and her ability to think and speak clearly, and at a place where she was in strong, gentle, trustworthy hands.

All at once, it dawned on me: My mother went peacefully — at a point before she completely lost her memory and her ability to think and speak clearly, and at a place where she was in strong, gentle, trustworthy hands. My family and I would never have to watch her slip any farther. She died with dignity and grace, and for that, I will always be grateful.

The crematory operator asked if I’d like to push the button. I said no thank you, that I’d like to take a walk and come back — but that I needed him to promise me that he wouldn’t touch her cremation ashes. I needed to know, without a doubt, that they were hers. He kindly agreed.

There was a cemetery behind the crematorium. As I strolled past people’s headstones — covered in plastic flowers, pinwheels and little stuffed animals — I had an epiphany: Here lie the remains of people who meant the world to their respective partners, family members and friends. Each and every one was of them was loved. Each and every one of them is missed.

When I returned to the crematorium, I looked in the retort at my mother’s ashes. I was shocked to see her bones — not just all the little slivers and fragments here and there, but some whole half bones — big and gorgeous and brilliantly white. The realization she was actually gone hit me hard. Yet there was nothing whatsoever about seeing her ashes that was macabre or creepy to me.

“Your mother burned really hot — 2,000 degrees F,” the crematory operator told me. Later, after I’d gotten home, I remembered that every time my mother — always a healthy, robust woman in life — went for a bone density test, her results indicated that her bones were exceptionally heavy. In hindsight, I wish that I’d asked to keep a small one of them. It would have served as a daily, tangible reminder of just how strong the woman who made me was — even after her death.

Seeing these pieces of my mother brought the unexpected and difficult yet vital realization that my mother is no longer on Earth as a living, breathing human being

Although seeing a loved one’s bones the way I did might sound frightening or macabre, I actually found it completely natural — not to mention essential to my grieving process. Seeing these pieces of my mother brought the unexpected and difficult yet vital realization that my mother is no longer on Earth as a living, breathing human being. Never again will I lay eyes on the person I knew her to be. Any photographs of her, any images of her that I hold tenderly and lovingly in my mind’s eye, are of a person who was and will never be again. This moment of realization marked my entry into a new phase of mourning: I began to come to terms with the reality that my mother, as I knew her, was, and will forever be, gone. It gave me the deepest sense of love for who she was when she lived and breathed.

I Had to See My Mother Dead at the Crematorium and No, It Wasn’t Macabre

I Had to See My Mother Dead at the Crematorium and No, It Wasn’t Macabre

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States