This week’s very special Opening our Hearts represents a collaboration between Judy Vasos and Aurora Wells. All material is part of the Rosi Mosbacher-Baczewski private collection — which she had saved for nearly 70 years before passing on to her son and daughter-in-law, Tony and Judy, at the time of her death in 2009. Thank you so much, Judy, for sharing these treasured documents with SevenPonds!

Rosi looking at letters from her parents with her daughter-in-law Judy and a cousin, two days before Rosi’s death in 2009.

When the war first broke, the beautiful city of Nuremberg trembled like a crystal glass, warning that the earth could unravel at any moment. In 1939, Hugo and Clemy Mosbacher sent their daughter Rosi to England, where she had located work as a domestic. As the tremors of Nazi persecution escalated, Hugo and Clemy fled from Germany to Holland in February of 1940. Finally securing visas to enter the United States, Rosi’s parents were to arrive in New York on the steamship the S.S. Veendam, May 11 1940.

That spring, Rosi came to New York and waited to be reunited with her parents at last.

However, a single day before Hugo and Clemy’s scheduled departure, the Germans invaded the Netherlands in a surprise attack.

The Mosbacher’s exit visas were blocked, and despite the exhaustive efforts of Rosi and other family members, Hugo and Clemy would remain trapped in German-occupied Amsterdam for three years.

Rosi Mosbacher-Baczewski saved 100 letters and postcards her parents wrote her during this time…

“We are so preoccupied with you, dear Rosi, we think about you so often, we share your cares… and as a consequence, we converse with you in writing as often as possible… I believe this has become an obligation for which we must be grateful. People are so quick to forget obstacles that have been overcome, and to take for granted what is new and good as easily as if it had always been there.”

– October 2, 1940 (when Hugo and Clemy still expect to be on their way to the United States in May)

After the German invasion of Amsterdam locks them in limbo, Hugo and Clemy’s early letters are beautifully written, delicately worded plots of escape. Documenting their trials and failures, the letters speak of great frustration, filled with love and longing for freedom and family — but repeatedly find solace and hope in the safety of their daughter. They wrote every week, and Hugo carried Rosi’s letters around with him wherever he went. They were a lifeline.

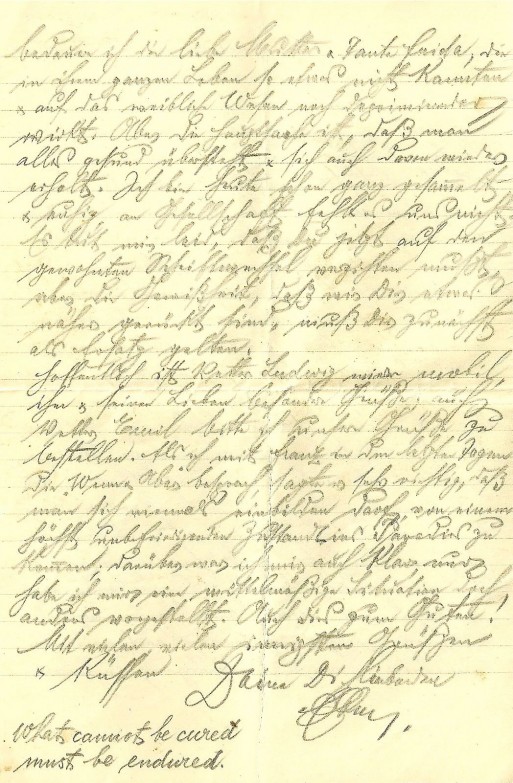

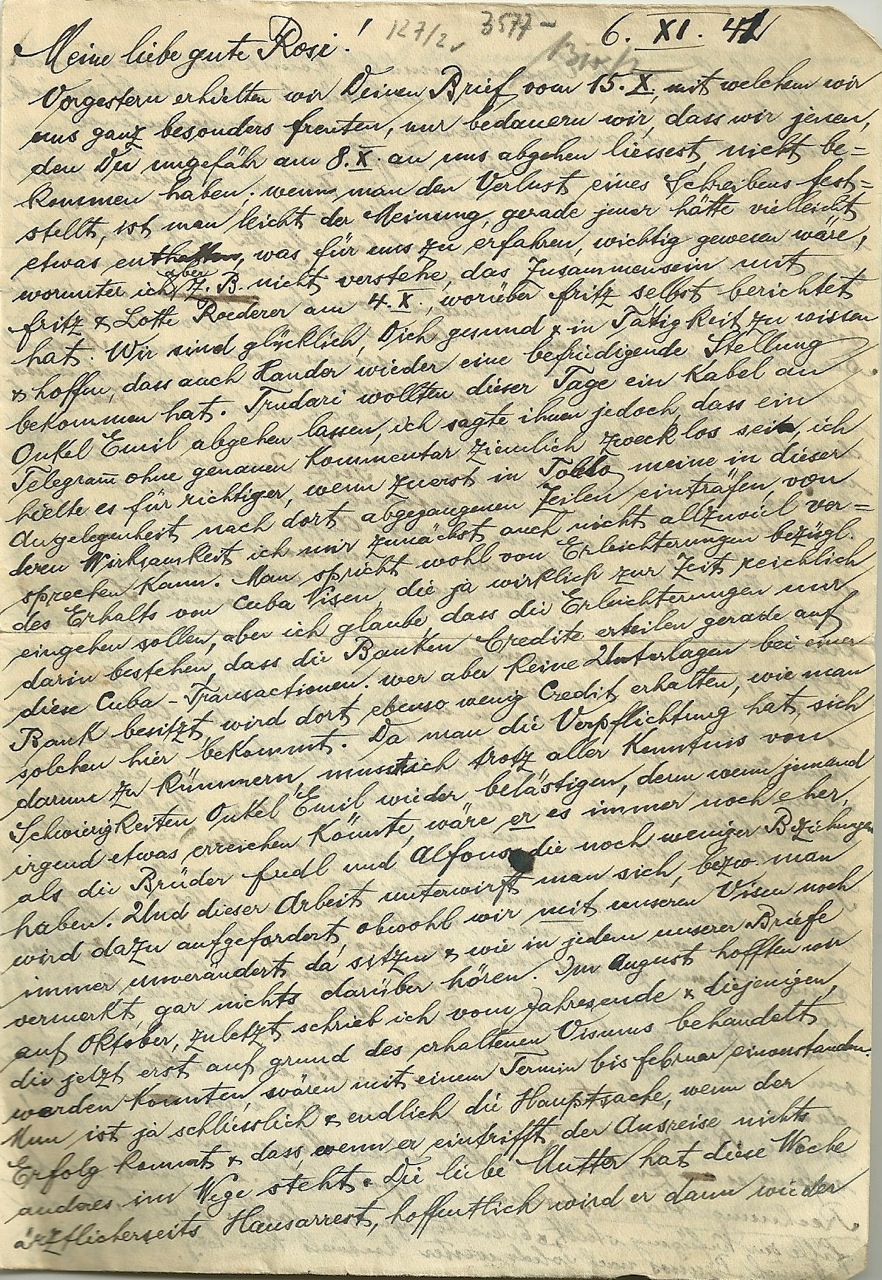

This is a letter from Hugo to “my dear, good Rosi,” written with a fountain pen. Note the German censor marks in pencil at the top of the page; every letter was opened, censored and marked before being sent to its destination. This delayed delivery significantly, as often discussed in their correspondence. It was always a relief and joy to receive another letter.

“Our pains are shared by many others. We have to keep telling ourselves we’re not the exception and must continue to find the patience… and we’re going to do it if we like it or not.”

“Still, we don’t want to complain and must thank God when we hear good things from you — and everyone remains in good health.”

– January, 1941

“There isn’t any point in talking about past mistakes, since our trip had already been so beautifully and perfectly planned and it would have been carried out if nothing had intervened. We’re not the only ones to be affected in this way.”

– February, 1941

A photo of Clemy and Hugo taken in Amsterdam and sent to Rosi in 1941. She kept it framed atop her bureau, always.

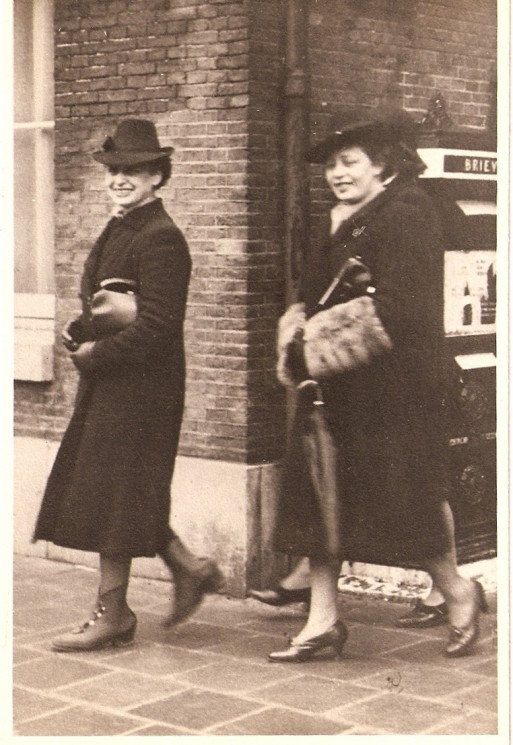

Clemy, left, with a family member.

The day of Rosi’s cousin’s civil wedding ceremony in Amsterdam, summer of 1942. Hugo third from left and Clemy far right. In Amsterdam, Jews were not yet required to wear the yellow star of David – but by the time of Rosi’s cousin’s religious ceremony a few months later, a star would be sewn on her dress.

Rosi fell in love with a man named Alexander, but wanted to postpone their wedding until her parents could be present. Reflecting increased resignation to an uncertain fate, Hugo and Clemy tell Rosi to go ahead with her wedding plans — and in July of 1942, Rosi married her sweetheart. Rosi’s parents wrote of Alexander endearingly, and he corresponded with them as well.

A letter written by Hugo. Note the quote in English at the bottom: “What cannot be cured, must be endured.”

In January 1943, Hugo and Clemy Mosbacher were sent to Westerbork, a transit camp in northern Holland. Two weeks later, they were put on a transport to Auschwitz, where, according to records kept by the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation, “they were killed immediately upon arrival.”

Rosi was 27 when she learned that she would never again receive a letter from her parents, let alone receive them in person.

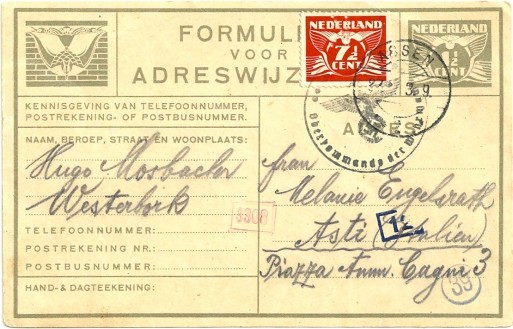

A change of address notice filled out by Hugo and sent from Westerbork Transit Camp, where he and Clemy were held for two weeks before being deported to Auschwitz.

That year, Rosi and Alexander had their first son, Tony — named after the little boy Rosi nannied in England. A second son, Steve, was born two years later. Tony and Steve only knew their grandparents through their mother’s memory… until the discovery of these letters and documents, many years later, brought Hugo and Clemy to life.

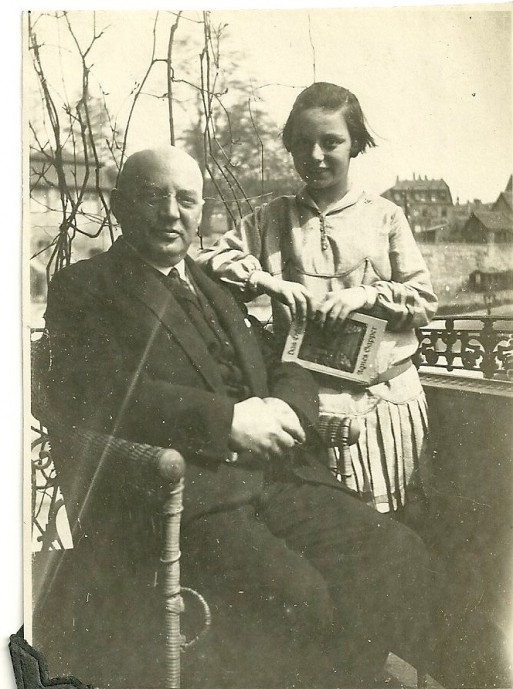

Rosi as a little girl with her father, Hugo.

And may their legacy live on.

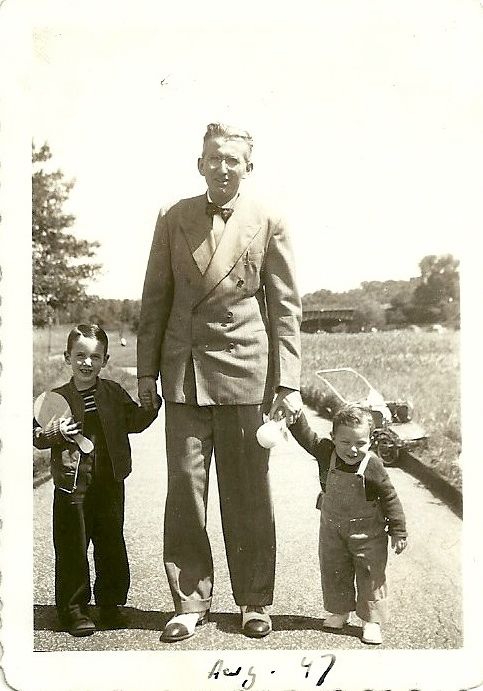

Rosi’s husband Alexander, with their two boys.

Letters from the Holocaust

Letters from the Holocaust

Mishap With Grandpa’s Ashes Highlights Growing Trend to Keep Cremains at Home

Mishap With Grandpa’s Ashes Highlights Growing Trend to Keep Cremains at Home

“Hello, Goodbye: 75 Rituals for Times of Loss, Celebration, and Change” by Day Schildkret

“Hello, Goodbye: 75 Rituals for Times of Loss, Celebration, and Change” by Day Schildkret