Humans and death have a complicated relationship.

With the widespread death and uncertainty the world has been forced to face over the last two pandemic-heavy years, it might seem only natural that death would rise as a cultural star.

And it would only be natural that our dynamic with it would be awkward.

As a society, we forever walk the balance between death acceptance and death avoidance. Over the last millennia, we’ve been one with it; we’ve made it taboo; we’ve worshiped it; we’ve legislated it; we’ve made art about it; we’ve profited from it; we’ve made it environmentally terrible; and we’ve made it “green”, and on and on.

Death is normalized and it’s not, all at once.

As an example, a New York Times article from September 2021 highlighted a slew of television series that have arisen in the last two years. Many focus on death and redemption, such as “Manifest,” “Glitch,” “Katla,” and “The 4400.” They explore the idea of one getting a second chance, or coming back to complete unfinished business, or revisiting relationships and regrets. Death may be featured in these shows, but it’s often just a plot device or the setting for a very “alive” storyline. Other shows along these lines include Amazon’s “Upload” and “Forever,” and Netflix’s “The Good Place” and “After Life.”

While thought-provoking, these series are primarily for entertainment — “an outlet for sorrow and remorse” with a little bit of escapism on the side. They won’t help you learn about end-of-life planning or prepare you to lose a loved one, but, then, they aren’t intended to.

Death in the Morning, Afternoon, and Evening, Please

Death as inspiration for entertainment, art, or fashion, from haute couture to toddler-wear is not new.

Baby clothes featuring the Grim Reaper can be found on walmart.com, cafepress.com, zazzle.com and more. This image courtesy of kidozi.com.

In 2015, anthropologist Dina Khapaeva published “The Celebration of Death in Contemporary Culture,” which explored the reasons for the rise of what she calls “the cult of death” in American entertainment and culture.

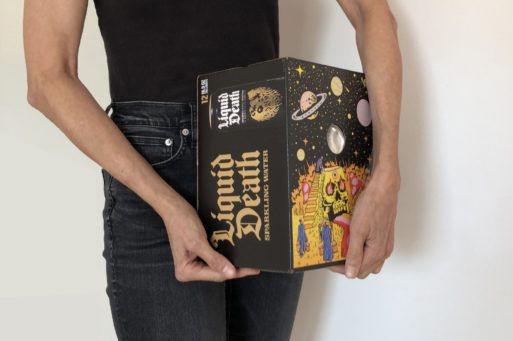

In an interview, Khapaeva states that the catalyst for her work came when she was shopping at a major retail store and noticed a clothing line for toddlers featuring skulls and crossbones and the Grim Reaper. And almost a decade later, you can still find Grim Reaper toddler wear, as well as a wide array of food and beverage brands brandishing the name of death, like Liquid Death Sparkling Water. I reached out to the CEO of Liquid Death to see why they named his water brand as such. I did not receive a response, but their website “manifesto” says they love humor and hate corporate marketing.

Boxes of Liquid Death Sparkling Water in a grocery store at the largest retirement community in the country, The Villages in Florida.

Other brands using death-as-disruption include the ultra-dark roast Death Wish Coffee, and alcohol brands Death’s Door Vodka and Crystal Head Vodka.

Aside from products and television series, there’s also more educational content about death. Some are focused on the biological facets of dying, like The Pre Dead Boys, which is about the history and culture of death and decomposition. Others aim to have frank conversations about grief, such as Terrible (Thanks for Asking), Good Mourning Podcast, and You’re Going to Die.

Thegriefspace_ is just one Instagram account that provides grief resources.

And of course, there’s the mixed bag of social media. Notably on Instagram, you can see tons of content and announcements by those in the death and end of life industry. There are hundreds of accounts associated with the word grief, alone, such as Thegriefspace and Talk Death Daily. There are also accounts like The Funeral Life, Mortician Memes and Funeral Memes, which just post “funny” memes about the funeral industry or embalming.

As a testament to the coolness of death, in 2013, the Atlantic published an article entitled “Death is Having a Moment,” interviewing then-29-year-old mortician Caitlin Doughty (who has been called a “hipster mortician,” and “macabre nerd”). Doughty said of the rising trend: “You have this critical mass of interest. Death is fascinating.”

This explains the Death Salon, co-founded by Doughty and Megan Rosenbloom. Death Salon is a multi-faceted organization that holds public events and discussions on ideas of death and culture. The events often include Edwardian-style balls that include the dress code “haute macabre.”

Death Salon in 2015 at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia

Credit: deathsalon.org, taken by Scott Troyan.

Doughty, also the author of three New York Times best-selling books, founder of the Good Death Institute, host of the YouTube series “Ask a Mortician,” and co-host of the podcast “Death in the Afternoon,” coined the term “death positivity” in 2013 on Twitter.

But death coming of age isn’t all macabre balls and scientific corpse talk. Nor is it just funeral memes or Netflix murder mysteries. Much like how sex has been used to sell things from cars to cologne while having zero to do with sex positivity, the coolness of death can also sell.

As with any movement driven towards change, the people who are involved are going to vary.

And like any movement, it’s going to have a history.

A Short History of Death & Dying Movements

Some have called the “death positive” movement the third wave of its kind, building on similar movements from decades past.

This may have begun in the 1960s, when Jessica Mitford’s “The American Way of Death” first was released, and when cremation began its rapid takeover of traditional burial. From 1960 – 2015, cremation rates rose by 1400% and overtook traditional burial nearly a decade ago.

This may have begun in the 1960s, when Jessica Mitford’s “The American Way of Death” first was released, and when cremation began its rapid takeover of traditional burial. From 1960 – 2015, cremation rates rose by 1400% and overtook traditional burial nearly a decade ago.

This preceded the United States movement towards hospice in 1969, when Dr. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross published “On Death and Dying,” identifying the five stages through which many terminally ill patients progress. A few years later, in 1972, Kubler-Ross testified at a national hearing on the subject of death with dignity. Also, during this time, the Association of Death Education and Counseling (or ADEC) was formed and remains one of the largest organizations dedicated to sharing knowledge and advancing practical care at the end of life. And in 1974, the first hospice in the United States, the Connecticut Hospice in Branford, Connecticut, was founded.

Betsy Trapasso, an end-of-life guide, advocate and former hospice worker in Los Angeles County, was intimately connected to this first hospice. “My grandfather was the mayor at the time, and he had to do a lot of lobbying and talking about what hospice is and so on in order to get funding. It took years, but he never gave up. I was 12 when it started and in high school when they finally broke ground.”

Later, after getting her Master of Social Work from the University of Southern California and working as a therapist, Trapasso herself became a hospice social worker. She described what it was like: “Thirty years ago, there weren’t cell phones, the internet or social media. I wasn’t trained in hospice — and I was the only social worker for my hospice and drove all over LA County. I learned by going into people’s homes. The dying taught me. Which, I think, is one of the best ways to learn.”

Betsy Trapasso, end-of-life guide and advocate started the first Death Cafe in Los Angeles.

Trapasso was a part of the death and dying movement before it was a “movement.”

“When I started it was like an island, not an industry. Getting the word out was much more difficult then. And now, social media is huge. Everyone can connect to each other — different groups are able to come together and work together, like palliative care and grief workers and green burial and tech. And now younger people are getting into it, learning about it, and getting more involved. There were no young funeral directors back in the day. They were all older. The bubble is getting larger, and I love the support we all give each other.”

When asked what was missing from the end-of-life bubble, Trapasso didn’t miss a beat: “Funding. Funding and support from the higher level for caregivers. There is grassroots support, but not support from the top.”

Trapasso herself has an idea for an Americorp-style volunteer organization in which young volunteers use their gap year to learn about end of life while providing much-needed support to caregivers in the field. “It’s so difficult to change laws and legislation, but people are really trying. Caregivers are telling their stories and people are listening. But burnout is real, and it’s only getting harder because a lot of mom-and-pop hospices have been bought out by large corporations, and the caseload gets bigger, and the nursing staff grows smaller, and memory care is so costly…”

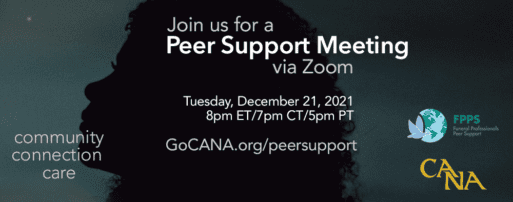

One example of grassroots support is a monthly peer support group for all death care workers organized by the Cremation Association of North America. I attended an online meetup in mid-2021 with 24 others from all over the United States and Canada. Attendees came from all walks of death care — chaplains, funeral directors, life celebrants, owners of crematories and more.

Some in the group had their cameras and mics on, actively participating. Others had their camera off and only participated via the chat. A few shared stories about how their week went, from frustrations with the job to worries about their impact to personal issues making the work more difficult. One participant shared how earlier that week she had placed a woman’s child and husband into the crematory. “I had never seen something like that. So much loss. Trying to help families through this time is something radical.”

Another participant said of the support: “Our emotions have been pushed under the rug for so long…thankfully as the years have gone by, we’ve realized that if we are not truly healthy mentally and physically, we can’t serve the families that call on us.”

Acknowledging the mental health needs of health professionals is most certainly a sign of death going modern. But in many ways, it’s still in its nascent period.

Who Will Care for the Dead and the Living?

In 2010, the non-profit National Home Funeral Alliance was started, following in the footsteps created by Crossings and Final Passages in the 1990s. They were some of the first organizations that began training and educating families and communities to care for their own dead and hold home funerals. Home funerals are often more affordable, intimate and environmentally friendly than industry-led funerals, emphasizing that the family maintains control in the days following a death, including care for the body, disposition, and more.

Members at a National Home Funeral Alliance conference with a decorated mock vigil coffin. Photo by Barbara McAfee.

According to Final Passages’ website, they were also the first nationwide organization to create a death midwifery and home funeral guidance training program.

Now, it seems, you can throw a stone and hit a death doula training program. Death doulas or end-of-life doulas help the dying transition peacefully by offering physical, emotional, psychological and spiritual support to them and their families. The International End-of-Life Doula Association, the National End-of-Life Doula Alliance, Doulagivers, the Doula Program to Accompany and Comfort, the Metta Institute’s End of Life Practitioner Program, and A Sacred Passing, are just a few of the many programs now available.

But they are not all created equally. Lashanna Williams, death doula, massage therapist, and executive director of the Seattle-based non-profit A Sacred Passing says of the trend, “The certification for a death doula is pretty unethical. You can get a death doula certification after a 3-hour crash course, you can also get one after 6 months with no volunteering, or you can get one after a 2-year program. There’s no body for accountability. This puts the weight of figuring out what you do or who to trust on the vulnerable people who need help.”

Williams addressed what was lacking in “death positivity” today: “We have intersectionality and we have overlap, and we need to address them.”

Williams added, “When looking or hearing about a good death specifically, it’s important to think of “for who?” Only for the people with money? More often than not, you have to have money and a home and more. A lot of the death positivity and changes in legislation happened when baby boomers — specifically older white men — started dying. But conversations about making care equitable are not happening. And it seems like it might be easier for people to have conversations about death, but not actually talk about what’s really uncomfortable.”

Sacred Passing differs from other training organizations in several ways. Williams explains, “The cost of our class covers a living wage for the teachers and supplies. We’re not here raking in the cash, because that’s not the intention. Many people say ‘I’m going to be a death doula, and that’s my job,’ which is a little precarious. People definitely can do it and get paid, and no shade to those who do! If you’re in a community of folks who have the means to pay for your care, then rock it. But my work is focused on people who don’t have money, and that’s the space I choose to work in. If we could get hospices to start paying for our care, so people who are already doing the work could continue doing it, that would be great.”

We Become What We Needed

In 2011, Ned Buskirk was organizing open mics in San Francisco, unofficially starting what would become a wide-reaching creative organization, called You’re Going to Die or YG2D, which has grown from a monthly open mic to include a podcast, grief workshops, musical performances, and advocacy work in prisons.

Ned Buskirk of YG2D at their sold-out 10th anniversary show at the Independent in San He is demonstrating the range of honest emotions shared on stage at their events.

Buskirk said of YG2D’s creation, “It comes out of this need for community space, and also to say their names and talk about their life and death and have your grief witnessed and witness others’ grief. My hope is that at a minimum when you’re a part of something YG2D, you feel more alive than you did before, and there’s a sense of the reminder of not being alone. I believe if we engage with mortality and our community, we will have a richer sense of being alive.”

Katrina Spade in a video illustrating the service of composing of bodies provided by her company Recompose.

Buskirk, who lost his mother to cancer in 2003, also talked of his own experience: “I was in my 20s, and once the funeral ended, it was over. I didn’t get the value of honoring her regularly. And now, I do get to talk about her life and death. We come out of a time where most of our parents were quiet about their grief and didn’t want to talk about their dying. And it seems so many people in the world are activated as a reaction to create what was missing for them. Things like Reimagine, the Order of the Good Death, and others — I would bet that those who run them are fulfilling a need — one that was missing from their own experience.”

We create what we did not have. We become what we needed.

Photo courtesy of Lashanna Williams

This is what has been driving innovations in death and dying since the 70s, 80s and 90s when the decades-long development of POLST started in order to give patients more control at the end of life. This is also what has driven the ongoing Death with Dignity legislation, as well as more people being open to discussing the concept of rational suicide and the rise of supportive organizations like A Sacred Passing’s, “A Place to Die,” and the “Final Exit Network.”

Fulfilling an environmental need is what has driven Katrina Spade’s business, Recompose. For the last decade, the company has been working to legalize the process of “natural organic reduction,” or human composting. Thus far, they’ve been successful in three states.

It’s also what’s driving the development of organizations like The Collective for Radical Death Studies, a collective of death scholars and students, death workers, death practitioners, and activists who serve as a source to think critically about how people of color and those from marginalized communities die, grieve, and are buried and remembered. Williams, executive director of A Sacred Passing, talked about their organization’s community death care model and anti-racist focus, “As a woman of color in this country, this focus is my life. It’s not a trend. Everything, including death care, is focused on joint liberation, especially the joint liberation of Black and Indigenous people.”

With these huge cultural and practical changes to how we approach end-of-life, one would think that death is fully out of the shadows.

But Trapasso and Buskirk are both quick to point out that the end-of-life world is, in a way, its own world. When you’re in the world, it feels all-encompassing — as if death really has come out of the shadows. But while the bubble is getting bigger, death has hardly entered mainstream American culture. As Buskirk summed it up, “It’s humbling to remember that there are people who just don’t care.”

Death Goes Modern

Death Goes Modern

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”