Life is fleeting, and death apparently eternal. Still life paintings that came out of the Netherlands in the late 1500s through the 1700s, known as vanitas, gather symbolic objects of death into a memorialized moment, halting the processes of both life and death in a tangle of visual thought.

What started out as paintings of skulls and skeletons on the back of portraits evolved into a genre of its own right, no doubt on account of the high mortality rates experienced in Europe through waves of the plague.

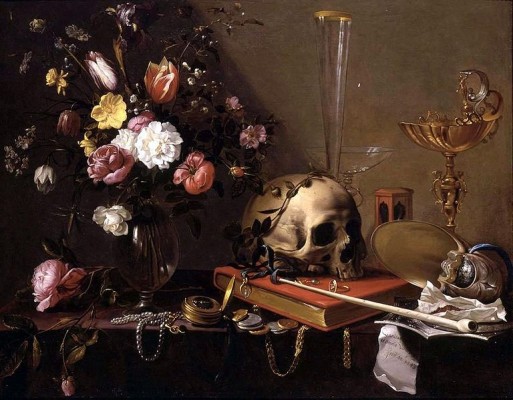

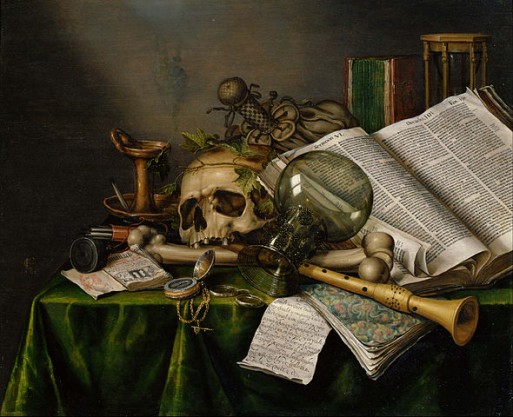

Vanitas, Latin for vanity, evoke the transience of life and the inevitability of death through a collection of symbolic objects. The objects highlight the futility of life by depicting the vacuity of earthly pursuits held in tension by objects of absolute finality: knowledge, in the form of books or maps; wealth, through jewelry or adorned objects; pleasure, through (empty) goblets or pipes. And the greatest force of them all, transience (death) through clocks, burning candles or a human skull.

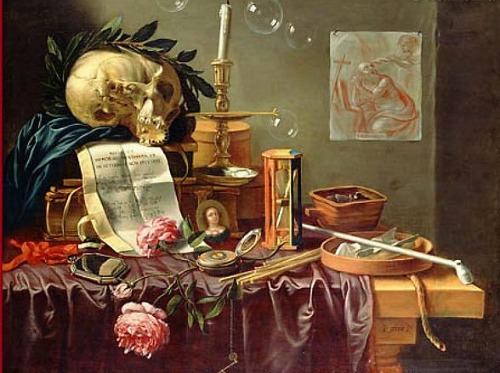

Oh, also, bubbles. Yes, bubbles.

The bubbles, like life, are precious and precarious, and could pop at any moment. They float suspended.

Each of the objects in a vanitas painting carries a symbolic weight, but their power comes in their collection in a frozen moment. A conversation begins to happen. We begin to attach stories to the assemblage.

Peter Sion’s vanitas is particularly lush. Large roses wilt across the table. A small portrait of a woman rests against an oversized book, potentially the portrait of a love recently lost. A candle flickers just out of frame.

This painting is full. It has all the vanitas elements. A candle, a book, an hourglass, a mirror, a skull. Bubbles. The objects are lush, over-ripened and over-saturated, to the point of drooping as if resigned to return to the earth. Even the cloth beneath the objects is deeply rendered and overstuffed.

Beyond the beautifully rendered objects sits a roughly rendered drawing of a man caught in a moment of prayer, turning his head in dread—mouth agape—towards a figure that approaches from behind.

But then something in the background creates a greater tension. Beyond the beautifully rendered objects sits a roughly rendered drawing of a man caught in a moment of prayer, turning his head in dread — mouth agape — towards a figure that approaches from behind. This drawing appears rough, frenzied and is highlighted by red strokes. The relatively calm, resigned moment on the table is overshadowed by the foreboding image above.

There is a sense of persecution in the drawing. Or interruption. As if while tending to one loss, another one befell the artist. Or maybe, just past the serene depiction sits the reality of a frenetic fear in the face of death and loss.

Plates of food and faces adorn later still lifes, as the subject matter move more towards life than death. But for a period, it was death that occupied the strokes of artists’ minds and brushes.

Later vanitas move from the morose palette of the early paintings into more light-hearted objects and warmer tones, and eventually incorporate people. Plates of food and faces adorn later still lifes, as the subject matter move more towards life than death. But for a period, it was death that occupied the strokes of artists’ minds and brushes.

One last painting by Edwaert Collier shows a scattered mess of objects on the table. The stilled moment is wild, chaotic and seems to be happening just as much as it has already passed. Much like life.

A Moment of Life and Death

A Moment of Life and Death

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento

Funeral Favors Offer Visitors a Tangible Memento