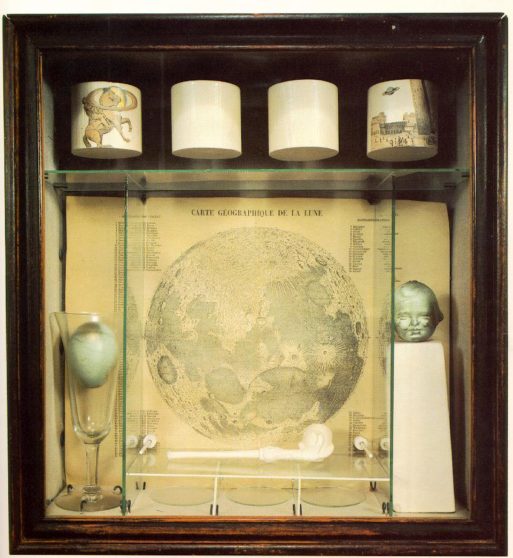

Untitled (Soap Bubble Set) (1936)

(Credit: ibiblio.org)

Joseph Cornell (1903-1972) is widely known as an American artist whose work influenced key developments in the contemporary art world, such as the Fluxus movement and the rise of installation art. His favored techniques of collage and assemblage using common, found and dime store items heralded the postmodern approach to artworks as an inquiry into the value of everyday/mass-manufactured items.

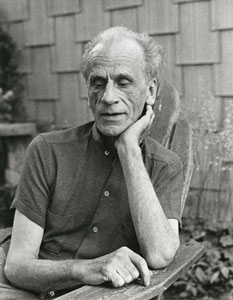

Joseph Cornell, American mid 20th c. artist

(Credit: derstandard.at)

Despite all the artspeak around this pivotal figure, there remains at the center of this story a man who lived his life in loneliness and anxiety. Cornell experienced alienation from society from an early age due to his father’s death from leukemia when he was 13 years old. This was followed by a financially disadvantaged youth, as his single mother took odd jobs to support her four children, the youngest of which lived with cerebral palsy. As the oldest of his siblings, Cornell was a quiet, studious and painfully shy youth. He studied for a few years at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, but he was never formally trained in the arts.

Cornell sought out self-education through the cultural institutions of ballet, theatre and fine art, but his participation even in these communities were from the perspective of an outsider looking in. His obsession with ballerinas and popular films; a passion for collecting and categorizing; and recurring themes of childhood and the cosmos convey a longing for connection, understanding, and shared experience expressed through his art. Supporting himself as a salesman and later as a textile designer, his oeuvre was created as a self-reflective process that cultivated safety, orderliness and a personal narrative that created belonging through association with abstract ideas, popular culture, and celebrity figures.

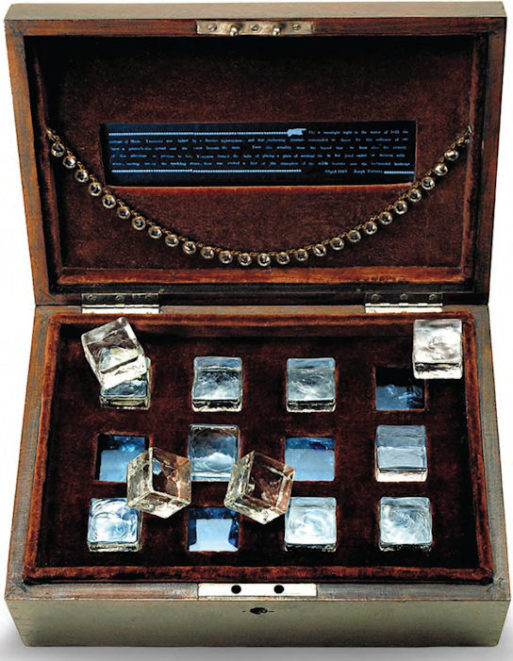

“Taglioni’s Jewel Casket” (1940)

(Credit: deliveryimages.acm.org/)

Cornell became a Christian Scientist in his early 20s based on his belief that the religion had cured him of a stomach ailment, and soon began to use the altar as symbolic place of prayer, remembrance, and pilgrimage in his work. His “boxes” — dioramas comprised of seemingly unrelated objects which appear to be linked by common themes and Cornell’s personal symbology — are complete worlds unto themselves. One might imagine looking at these works that the process of assemblage involved the creation of a universe with meaning and purpose. “Untitled (Soap Bubble Set)” for example, is the first of a series of boxes that have been viewed as a family portrait in which each item symbolizes a member of Cornell’s family. “Taglioni’s Jewel Casket,” on the other hand, is a fetishistic meditation on a legend about the 19th century ballerina Marie Taglioni, who kept a glass ice cube in her jewelry box as a memento of the time a Russian highwayman asked her to dance on an animal skin laid on a snowy road.

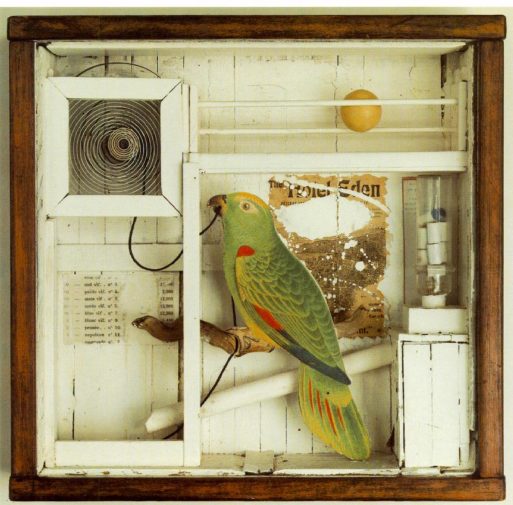

Untitled (The Hotel Eden) (1945)

(Credit: ibiblio.org)

Living with and caring for his invalid brother and mother until their deaths in 1965 and 1966, respectively, Cornell created in his free time the worlds of fantasy and respite that enlivened his imagination and kept him connected to the vast mystery of the world. “Untitled (The Hotel Eden)” speaks to this time-out-of-mind place, evoking a sense of whimsy and amusement. The lithograph-on-wood bird figure has no other care in the world but to amuse itself with the string in its beak; the orange sphere in the top right corner has a sense of resting in the perfect place.

Cornell’s work is an incredible example of how there is no right or wrong way to allow your life to be transformed by grief — by longing, loneliness, and the desire to escape reality by breaching the confines of the mind. His boxes are a study on the altar form, gridding personal memory, and experience with a cogent internal symbology that resonates with universal themes that connect individual to collective experience. Art therapists, psychologists, educators, and lay people may consider using this form to explore personal narratives, as well as a means to develop the core of a memorial altar or event.

Altars of Loneliness: The Art of Joseph Cornell

Altars of Loneliness: The Art of Joseph Cornell

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull