Eva Hesse’s (1936-1970) artwork is falling to pieces. The industrial materials that she worked with – latex, fiberglass, plastic – are deteriorating. They have a limit to their life and show signs of this. The fiberglass resin, which Hesse chose for its transparency, has darkened. The latex layers that she built up 40 years ago flake off or ooze amorphously.

The chemical instability of her chosen materials poses a problem for the museums tasked with both preserving and sharing her work. It is challenging to exhibit deteriorating forms, and even harder to transport them. For this reason, her work isn’t often seen publicly — it is safely stashed in museum collections.

What would Hesse make of this continued dissolution? Would she care that the brittle layers of resin in “Sans II,” for instance, flake away? Would she want it hidden and highly preserved? Or would she want it to stand as-is, vulnerable and expiring?

We are left grappling with Hesse’s body of work on several fronts; we want closure where there can’t be. Hesse produced work for 10 years, and then died of a brain tumor in 1970. She was only 34 years old. As she stated, “Life doesn’t last, art doesn’t last.” Art imitates life, painfully and forcefully.

“Life doesn’t last, art doesn’t last.”

I was fortunate to see “Sans II” in person at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2002. The piece inhabited the gallery space. Layers of latex formed organized boxes, living and breathing, expiring in the gallery.

I was suddenly, acutely aware of my own organized flesh. Her work surfaced an awareness of my material impermanence. It danced with my tenuous ability to wrap head and heart around ephemerality. We existed together in that moment, and in the next moment we changed. Living and breathing, we both inched our way towards death. Towards an unknowable state.

We existed together in that moment, and in the next moment we changed. Living and breathing, we both inched our way towards death.

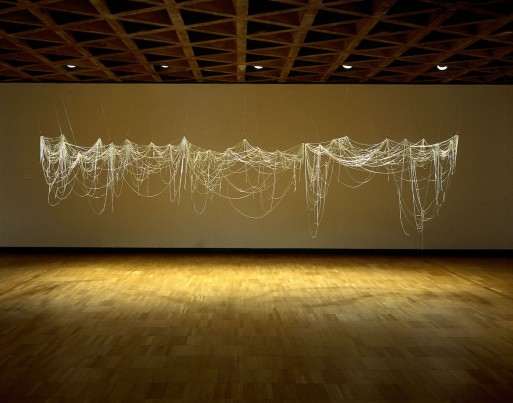

Hesse’s material’s inherent instability builds a conceptual frame as it comes undone. “Right After” drips with a visceral and vulnerable knowledge. Fiberglass, polyester resin, latex and cheesecloth intertwine like intestines and hang from the ceiling, suspended from hooks placed across a gallery’s expanse.

The material seems delicate as it radiates bodily presence, subject to the same forces that any body is subject to. We see gravity and the incessant movement of time, as the material hangs in the slow, sure progress of deterioration.

The knotted resin strips resemble a net of trash flung haphazardly across suspended lines. From something profane — from the bowels or the gutter — arises an odd beauty with emotional force. Soft, knotted, knowing.

Hesse infused her work with emotion without sentimentality, foregrounding the body without the tangles of a gendered politics. Her work hits a universal by striking individual chords.

In her short, 10-year period of artistic production, Hesse worked her way through the male-dominated art circles of New York, creating an estimable body of work and establishing herself as a potent postminimalist artist against a tide of male chauvinism.

The tragedies that punctuated Hesse’s life are often woven into discussions of her work. She was born in Hamburg, Germany in 1936 to observant Jewish parents, and her family fled Nazi occupation in 1938. She and her sister escaped on the kindertransport, and the family was separated for several months. Once reunited, they migrated to New York City where Hesse would later pursue her art. Shortly after her family arrived in New York, her parents divorced and her mother committed suicide a year later in 1946.

For Hesse, life was transient, even absurd, and single moments held meaning, the traces of which we see in her material forms. Her work was meant to expire, to fall apart just as our own bodies do. Her choice in material reflects this. In this way, we see a moment as built layers that fall away. In falling away, in grappling with the awareness of loss of our own material form and the forms of those around us, we too come into being as we fall to pieces.

If you live in San Francisco, you may be able to visit two of Hesse’s pieces, “Sans II” and “Untitled or Not Yet” when SFMOMA reopens in 2016.

Dissolving into Form

Dissolving into Form

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

“Hand to Earth” by Andy Goldsworthy

“Hand to Earth” by Andy Goldsworthy