Precious pigments: blues and reds were expensive paint colours reserved for the church, or the wealthy. Photo credit: Wikipedia

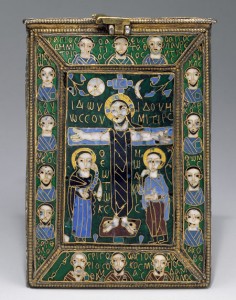

Time has turned the Byzantine Empire legendary from a grand successor into a struggling Roman Empire. Even if you can’t point to its capital on a map, odds are you’ve heard of the famed city of Constantinople. Known as “The Rome That Never Fell,” the Byzantine Empire encapsulated a kind of unparalleled religious and aesthetic grandeur, as evidenced in the relics it left behind. As a religious state, the Empire became especially adept at crafting intricate, cloisonnéd Christian reliquaries. Christ’s image was often bedecked in silver and precious stones by artisans, while the Virgin Mary’s silhouette was painted in gold (a Byzantine technique known as chrysography). This same element of splendor defined their portraits of saints and relatives who had passed away, with ornate tombs featuring portraits of the dead as standard practice.

“Christ’s image was often bedecked in silver and precious stones by artisans, while the Virgin Mary’s silhouette was painted in gold”

With the black plague wreaking havoc in Europe, there was an odd juxtaposition of extravagance and tragedy during the Byzantine Empire – specifically in the coexistence of death and splendor. On one hand, you have a religious Empire that believed in incorporating lavish materials into the worship of God, an activity that consistently defined the life of a Byzantine citizen. But with so many people dying, the very un-glamorous hardships of death also became a part of everyday life. It’s just one of the reasons, perhaps, that funerary Byzantine portraiture depicted loved ones as if they were still alive on their sarcophagi.

Reliquary of the True Cross. Cloisonné enamel, silver, silver-gilt, gold, niello. Photo credit: metmuseum.org

In…1348 the deadly plague broke out in the great city of Florence…Whether through the operation of the heavenly bodies or because of our own iniquities, which the just wrath of God sought to correct, the plague had arisen in the east some years before, causing the death of countless human beings. It spread without stop from one place to another until, unfortunately, it swept over the west…Such was the cruelty of heaven

—Giovanni Boccaccio’s description of the plague, The Decameron

Byzantine Christians believed that the archangel Michael presided over the soul’s separation from the body. During a three day period, he commenced the beginnings of what would ultimately lead to the Last Judgment – a moment that deemed you worthy of heaven, or hell. “Among the most elaborately decorated funerary monuments in medieval Byzantium was the niche tomb, or arcosolium,” states the Metropolitan Museum of Art; “[it] was set against the church wall and framed a sarcophagus below. Portraits of the deceased alone or in family groups popularly decorated such arcosolia.”

Related SevenPonds Posts:

- Walk Like an Egyptian: The Art of Grieving in Ramose’s Tomb

- The Queen and King of the Greek Underworld

- Bizarre Death Ritual: 19th Century Buddhist Self-Mummification

The Art of Death in the Byzantine Empire

The Art of Death in the Byzantine Empire

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States