Phowa (sometimes written as Poa or Powa) is a meditation technique of the Drikung Kagyu order of Tibetan Buddhism, and is practiced widely in all lineages. The Drikung Kagyu includes the complete practices and teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha, as well as the practices of the Five Profound Paths and the Six Yogas of Naropa. Phowa is known widely as the “transference of consciousness at the moment of death,” and is the fastest way to obtain an enlightened state.

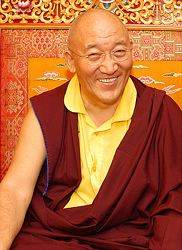

Phowa has been described in many ways, but the most important thing for Westerners to keep in mind is that it does not require anyone to give up their existing religious beliefs or traditions. It is, rather, a way to move energy and consciousness through the body; the visualizations used to meditate upon ultimate truth and totality will in fact differ from person to person. Choeje Ayang Rinpoche, a contemporary Lama well-known for teaching the practice of Phowa, describes this individuality in visualization.

The central element of Phowa practice is the cultivation of the ability to move one’s own consciousness (and with time, that of others) through the physical body up through the crown of the skull and out. This may sound like self-annihilation, and in a way, it is. Buddhists use Western science to explain: the human body completely renews itself at a cellular level every seven years, but most healthy people have memories from before that time. Therefore, consciousness is not inherent in the physical form, and exists independently of it. Phowa practices help the individual to know this on an experiential level.

The practice of Phowa is taught exclusively by Lamas initiated into the Drikung lineage, though any person is able to learn, practice and obtain the benefits for themselves. The results of Phowa can be obtained instantaneously in this lifetime, and the practice itself prepares one to encounter one’s own death with great equanimity, knowing that the self doesn’t die with the body. So, Phowa can be practiced in two ways: the first is to practice and obtain the fruits of this tradition for oneself, and the other is to facilitate this enlightenment process for another person at the moment of death. The latter requires the practitioner to be well-established in their own Phowa in order to be successful.

The curious can learn more about Phowa practices in the Tibetan Book of Living and Dying. Read about Phowa’s historical context and associated cultural traditions and receive the Phowa transmission through one of Choeje Ayang Rinpoche’s international offerings.

Phowa: A Tibetan Buddhist’s Conscious Dying Meditation

Phowa: A Tibetan Buddhist’s Conscious Dying Meditation

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

John Mulaney’s “Funeral Planning” on Netflix: No Real Plan

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States

Composting Bodies Is Now Legal in a Dozen States